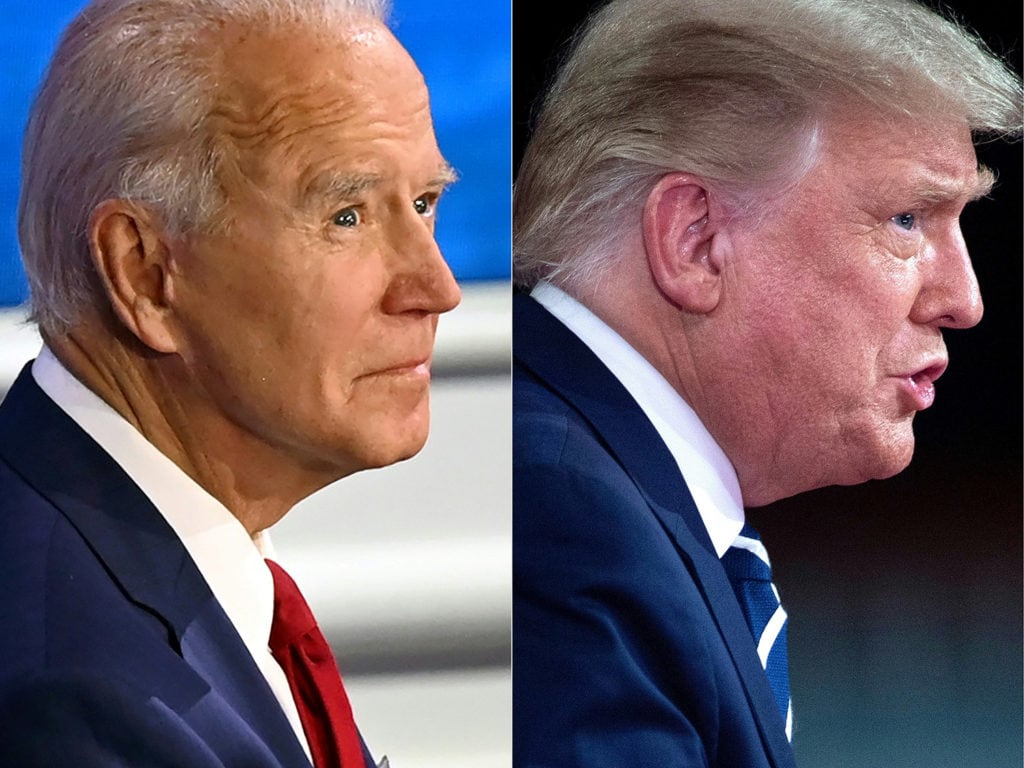

Biden succeeded in denying a second term to President Trump and his running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris, will be the first woman vice president.

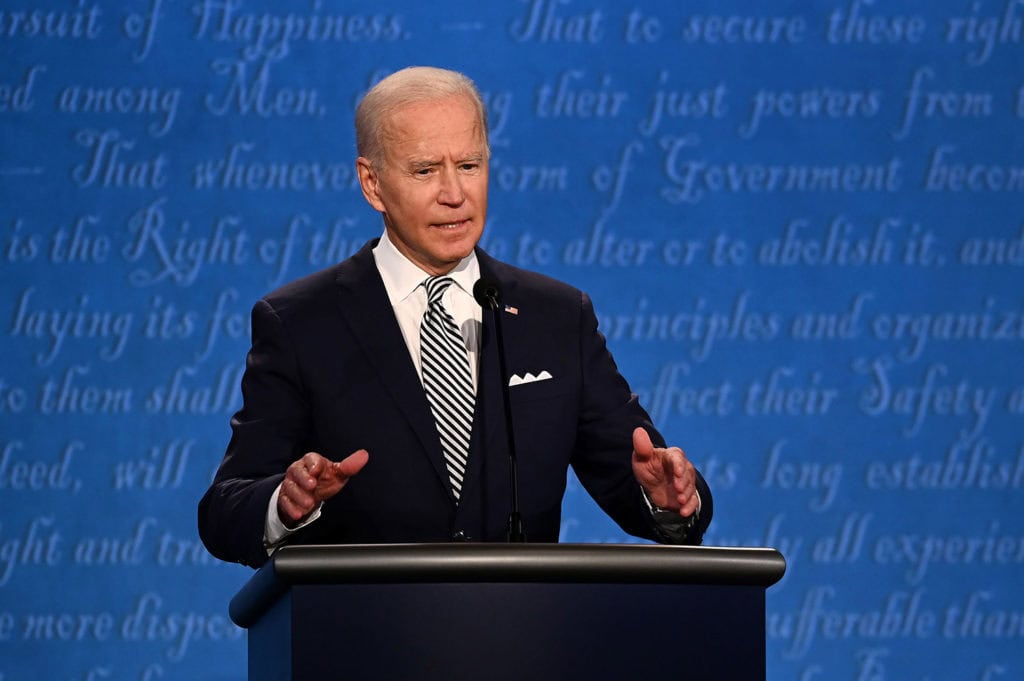

Joe Biden will be the next president of the United States, The Associated Press projects.

Some 18 months after launching his third presidential campaign — and four days into what had indeed turned out to be a protracted count of millions of mail ballots — Biden has won the election and denied a second term to Donald Trump, whom he said was poisoning the soul of the nation and, through gross mismanagement of the novel coronavirus, letting Americans die by the tens of thousands.

As of Saturday morning, the AP had projected Biden won 284 electoral votes to Trump’s 214 — above the 270-vote threshold — including the swing states of Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, with additional leads in Georgia and Nevada.

In his running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, Biden brings with him a history-making vice president as well: the first woman, the first Black person and first person of Asian descent to hold the office.

Biden had cast the contest in no less than existential terms and said his win would mark a corner turned toward conciliation after a year of widespread death, social upheaval and bitter recrimination, epitomized by the president himself (and his Twitter feed).

The win also comes with its own bruises. Biden’s elder son, Beau, died of brain cancer in 2015 — too soon before the 2016 presidential race, as Biden said his focus needed to be on his grieving family — and the 2020 election involved a price for younger son Hunter as well, whose personal scandals were picked over by a Trump campaign intent on making him a villain and his father a corrupt accomplice.

With voter turnout shattering records, the 2020 election may well be remembered as one of the nation’s most consequential contests.

Certainly it was one of the most historic, now eight months into a deadly pandemic that has come to define a race Trump had hoped to wage on his own terms. Instead, the president presided over a year in America in which more than 230,000 people were killed by the coronavirus, the economy cratered unlike it had in decades and cities nationwide were roiled by demonstrations and riots sparked by racial injustice and police misconduct as Trump reacted with vehement, even racist, disdain.

While Trump had planned to campaign on a roaring pre-pandemic economy while painting Biden’s Democratic Party as a Trojan horse for left-wing radicals, he was left to grapple with months of voters’ focus on the coronavirus and how their lives had been upended after a summer that underlined the nation’s ugliest racial tensions and history of inequality.

At times this year the president struck varying tones of resolve and unification, and saw brief bumps in support as a result.

But as his original strategy unraveled amid the pandemic, Trump — whose provocative and pugilistic style helped carry him to the White House four years ago — harkened back to that successful campaign by ever-more-relentlessly arguing that Biden and Biden’s family were double-dealing insiders unfit to govern and he envisioned an America with him out of the White House in which lawlessness reigned.

As Election Day approached, Trump also insisted the results might be fraudulent and that he might not accept defeat — a stunning and undemocratic turn for a sitting president, and one which he embraced in the days after polls closed and more and more votes were counted for Biden.

Throughout, Biden styled himself as Trump’s opposite: a Democrat, yes, but also a uniter with famously open heart.

In August, he made history by naming Sen. Harris as his running mate. (Biden, who will be 78 when he is sworn in, has studiously avoided discussing how age might affect his future though Harris’ nomination was widely seen as an anointment of the next generation.)

“We’ve got a lot of work to do,” Biden said in his final pre-election speech, Monday night in Pittsburgh. “Not division and distraction, but the real work of healing this country.”

He said as much again on Wednesday, a day after the election and with the results still being finalized.

“I will work as hard for those who didn’t vote for me as I will for those who did,” he said then. “Now every vote must be counted. No one is going to take our democracy away from us. Not now. Not ever. America has come too far. America has fought too many battles. America has endured too much to let that happen.”

The pitch, as Biden himself noted, was the same one he’d been making since April 2019 — long before the shadow of death cast by a new virus that Trump repeatedly downplayed and long before the uncertainty and anxiety of 2020. But already, in Biden’s view, far too long under a president more interested in himself than in anyone else.

“Americans are facing a confluence of crises unlike anything in living memory and we are still in a battle for the soul of America,” Biden said Monday. “But let me tell you something, folks — tomorrow is the beginning of a new day.”

Election Day dawned with yet more history made, as some 100 million Americans had already cast their votes in a tidal wave of early balloting — reflecting both intense interest in the presidential race and droves of new mail ballots amid the pandemic.

Turnout skyrocketed higher still on Tuesday, eclipsing the 138 million people who voted in 2016.

That year’s race, between Trump and Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, saw the real estate businessman and former Apprentice host eke out a surprise victory thanks to razor-thin margins in the upper Midwest. The 2020 campaign was fought across some of that same ground — in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — though the Biden campaign pressed its advantage against Trump’s unpopularity to try and expand into formerly Republican states like Arizona, Georgia and Texas that had increasingly started lightening to blue.

In the end, Biden earned crucial wins in the Midwest and in what had been Trump country, though Trump triumphed in Florida, Ohio and Texas.

While Trump increasingly dismissed the pandemic — even after he was hospitalized in October with the coronavirus as it swept through his family and his inner circle — Biden and his team had used their contrasting approach to build support from voters who consistently said the virus was a major issue and who regularly voiced concerns with Trump’s temperament and trustworthiness.

The same lawmaker who commuted back-and-forth miles on Amtrak as a senator so he could be home with his boys at night was diligent about following medical and scientific guidelines for mitigating the spread of COVID-19. He regularly wore a face mask when he was near others — as Trump mocked him for it — and his campaign invented drive-in rallies to allow for a socially-distanced crowd at parking lots across the battleground states.

In a foreshadowing of Trump’s eventual defeat at the ballot box, the Republican coalition had severely eroded during his years in office, with suburban and college-educated white voters in particular flocking to Democrats even as Trump made notable gains on what had been barely-there support from Black and Hispanic voters, particularly in ever-close Florida.

Adding to the unprecedented nature of the 2020 race, Biden’s bid was joined — with a vengeance — by thousands of GOP stalwarts disgusted by what they saw as Trump’s hijacking of their party and its small-government, fiscal-conservative values. Groups like The Lincoln Project and 43 Alumni for Biden comprised of aides to George W. Bush’s White House, formed to raise millions of dollars and air against Trump and his congressional Republican allies — in a targeted state-by-state strategy — some of the most scathing political ads ever produced.

“The party we once called home exists now as a corrupted shell of its former self, informed by neither principle nor philosophy. It is a political Chernobyl — radioactive and dangerous but with a still unknown half-life,” The Lincoln Project founders wrote in a campaign-homestretch op-ed.

“The Biden era,” the group’s column continued, “… will be a return to an America where we face tough problems together, do the hard work of governing for the good of all Americans, where compromise is considered a goal, not an accusation.”

It was in some ways a man meeting the moment, at least in the view of Biden’s supporters: The boy from Scranton, Pennsylvania, turned longtime senator from Delaware turned loyal vice president to Barack Obama; the grieving father and, to much of the nation, folksy (if gaffe-prone) “Uncle Joe” who has long been shadowed by loss.

Widely viewed as a centrist Democrat with a knack for building relationships and consensus, Biden launched his latest bid last year and has been making the same argument for himself ever since: The election, he said over and over, is about unity — a repudiation of what he called Trump’s toxicity.

(The race has not been without blows for Biden as well, including challenges in the Democratic primary over his previous positions and — most seriously — a sexual assault allegation by a former Senate aide who worked for him decades ago, Tara Reade, which he and others from his office in that time have forcefully denied.)

It remains to be seen how and how quickly the country might cohere: The president was unfailingly unpopular during his four years in office but never shed a significant minority of support from Americans. Trump will not leave office with the same sense of repudiation as former presidents Bush or Jimmy Carter and he has suggested a next act much like the last, with future rallies and Twitter commentary.

And while Biden earned higher marks on favorability and trustworthiness than the previous Democratic nominee, he faces hurdles in implementing his legislative agenda with a still-recovering economy and the threat of the pandemic — a priority, according to health experts — hanging over the nation.

[People]